In December 2024, I visited the Keezhadi Museum to explore its extensive collection of antique beads excavated from nearby sites. Within these small yet intricate artefacts lies the story of a civilisation that flourished along the banks of the Vaigai River. The coins and beads along with other artefacts displayed in the museum offer a fascinating glimpse into the fashion and lifestyle of the Sangam-era people. Their aesthetics, craftsmanship, and material choices whisper secrets of an advanced society deeply engaged in art, trade, and technology.

Jewellery as a Marker of Civilisation

Finding jewellery and beads at excavation sites is a common occurrence worldwide. Beads, often found in burial sites, provide crucial chronological markers through carbon dating. But beyond their age, they serve as invaluable windows into the material culture of those who made, traded, and wore them. Each bead tells a story—of knowledge passed down through generations, of economic exchange, and of a people’s sense of beauty and identity. They serve as a testament to the region’s prosperity and its deep-rooted connections with civilisations far beyond its borders.

The advancement of any civilisation can be understood through its script, urban planning, and appreciation for the finer things in life. The presence of meticulously crafted beads in Keezhadi suggests stability, prosperity, and extensive trade networks that brought in exotic materials from across the subcontinent and beyond.

Fashion and textiles at Keezhadi

The textile and jewellery gallery at the museum presents an intimate portrait of ancient Tamil life. Terracotta spindle whorls, spinning needles, terracotta cups, and weaving weights stand as silent witnesses to the mastery of Tamil weavers. These whorls, used for spinning delicate cotton and silk threads, have been used to spell out Thugil—the Tamil word for fine fabric along with the Indian Handloom Mark. Through this, the curators seem to be reminding us that Keezhadi’s weavers created some of the finest textiles of their time, as referenced in ancient Sangam texts.

The earliest fabric found (at Kodumannal) is 2500 years old. Ancient words such as thuni for cut cloth (yardage) and madi for folded cloth are a part of the contemporary tamil language as well. Men wore light coloured fabrics wrapped around their waists (similar to the present-day veshti), with a thundu or angavastram (towel or upper cloth). Women wrapped themselves in fabrics comparable to the present-day sarees. The length and the drape of the saree and veshti depended on their status and profession.

The animations at the museum show women wearing a kacchai/kaccham (breast band style blouse) and a sirupudavai/surrupudavai (short saree) which reaches mid calf. The short films also indicate the extensive dyeing techniques and colours used by the people. This could have been influenced by texts such as Silappathikaram that discuss dyeing with cochineal (indragopam) in the streets of Madurai.

International Trade

Keezhadi’s artefacts, including Roman coins, weights, and beaded jewelelry provide compelling evidence of its extensive trade networks. The presence of domesticated horse bones and perforated pots suggests commerce with Arab merchants. Many of the beads displayed in the museum originate from North and North-Western India demonstrating the trade connections of ancient Tamil society.

Diversity of beads at Keezhadi Museum

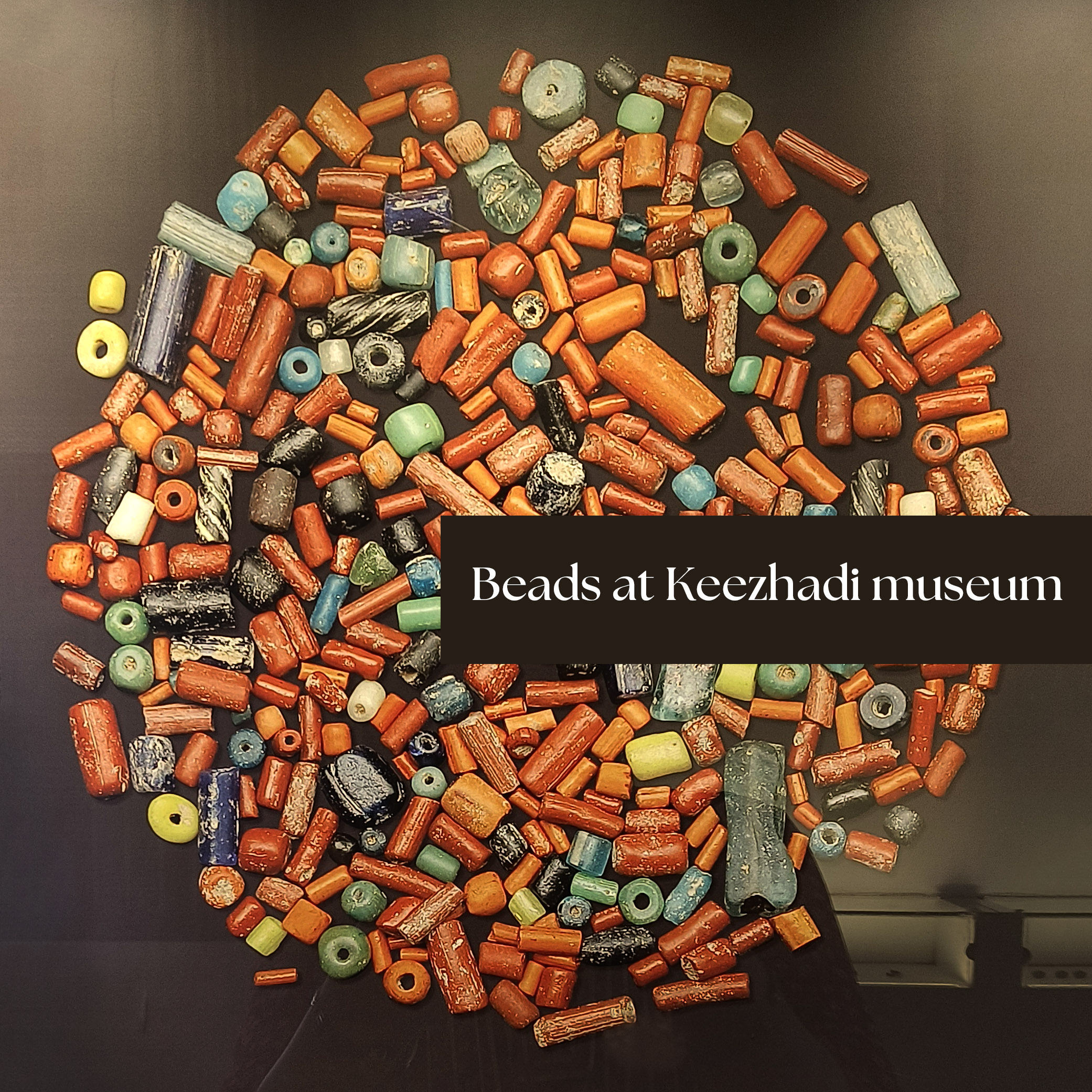

In the cool glass cases of the museum, an astonishing array of beads glimmers under the lights. Agate, carnelian, faience, soapstone, and glass are arranged beside chunky crystal quartz (Spatikam) and amethyst (Sevvandhikal). Rows of faceted beads suggest an advanced level of craftsmanship that surpasses my expectations. Each bead—round, oval, tubular, bicone, disc, in smooth and faceted forms seems to whisper a lost aesthetic language. The presence of gold components in the precious ornaments section – a flower component, a bead, some wire, and a dangler that could have either been a pendant or an earring is fascinating.

Watch a museum video on stone bead making below. You may turn the auto-translate into English or your language of choice for closed captions if you do not understand Tamil.

The video above discuss stone beads in general without a specific mention of which gemstone bead was produced by this firing process. Exploring this could offer new insights into early Tamil bead making techniques.

Glass beads at Keezhadi appear in reds, oranges, blue, green, and yellow. Madurai was an important pearl trading centre and texts describe gemstones such as diamonds, corals and rubies as well. I wonder if and when we will find archaeological evidence of the same. The absence of lapis lazuli, a gemstone prevalent in the Indus-Saraswati civilisation is noteworthy.

The Carnelian Connection

Carnelian, known as Sudu Pavazham in Tamil, appears to have been particularly prized. A remarkable discovery at the excavation site in Konthagai revealed 78 carnelian beads nestled within a burial urn. Two bear etched patterns ofparallel lines and chevron stripes. Ayesha Hina’s research on Harrappan artefacts at Gandi Umar Khan may provid a deeper insights into their significance.

The museum categorises carnelian beads by colour, displaying 125 specimens in bright orange on display. These carnelians, sourced from Afghanistan, Gujarat, Maharashtra, and Rajasthan, underscore the extensive trade networks of the period. The ancient Tamil text Paṭṭiṉappālai (verse 187) by Kadiyalur Uruthiran Kannanar which describes the lifestyle of people at the ancient port city Poomphuar (Puhar) refers to “beads and gold from the northern hills,” possibly alluding to such items.

Shell Bangles

The first time that I came across a description of Tamil women wearing shell or conch bangles was when I read Silappathikaram. Until then, I thought that only Bengali women wore them as Shanka-Paula (Conch and coral bangles). It is both fascinating and worrisome to note the practice of wearing these bangles has disappeared from Tamil Nadu.

A museum video below that details the intricate shell bangle-making process. Watching the craftspeople carve and polish conch shells into luminous rings makes one appreciate the delicate labour behind these adornments.

Glass bangles, though broken into fragments, hint at a culture that appreciated ornamentation. Their glossy surfaces catch the light, conjuring images of wrists adorned in clinking colours.

Terracotta jewellery

In addition to gemstones and glass, terracotta beads have been unearthed, highlighting the use of locally available materials in ornamentation. The drawings are fascinating and makes me wonder about how they would have been worn.

Reconstructing Ancient Jewellery Designs

At the museum, beads have been strung into simple necklaces, grouped by colour. However, I suspect that the original jewellery designs would have been far more intricate. The animated films playing in the museum depict women wearing sirupudavai (a short saree-like garment), gold earrings, shell bangles, and beaded necklaces. While each element depicted has been found in excavations or referenced in Tamil texts, I suspect the illustrations lean more towards contemporary attire with minor historical modifications rather than an accurate reconstruction of 800 BCE fashion.

Where to see beads at the Keezhadi museum

The museum houses beads in four different galleries:

- Textile and jewellery Gallery (First Floor): Exhibits a variety of glass, soapstone, crystal quartz, carnelian, and amethyst beads.

- Trade Gallery: Showcases banded agate and carnelian beads alongside Roman and other foreign coins and trade weights.

- Pottery Gallery: Displays beaded necklaces, ivory combs, and fragments of glass and shell bangles.

- Final Gallery (Near the Exit): Features terracotta beads, terracotta ear ornaments, and gold findings.

From carnelian and agate to glass and terracotta, the beads at Keezhadi museum tell a story of commerce, artistic expression, and cultural evolution. As I walked through the galleries, I couldn’t help but wonder what other secrets lie beneath the soil, waiting to be unearthed. Keezhadi is not just an archaeological site. It is a bridge to our past, inviting us to reimagine the lives of those who shaped early Tamil history.

Do check out my previous post on a trip to the Keezhadi museum to learn more about the museum.

I hope you find it interesting

Cheers

What do you think?